Michigan Terminal System

Last update: June 27, 2022 15:52 UTC (0f00b1f22)

During much of the 1960s I was a staff member at the U Michigan Computing Center. I worked with a bunch of other guys on various hardward and software projects, one of which is described on this page.

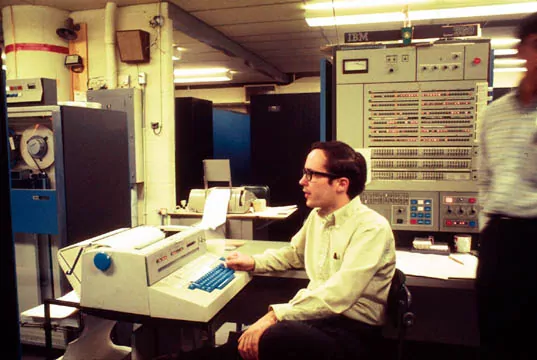

The Michigan Terminal System (MTS), along with Multics at MIT, were the first operational virtual memory operating systems in the world. The pictures here, taken circa 1969, give some idea of the computing systems of that era. IBM was the crushing giant, affectionally called Big Blue, or International Bull Moose. At Michigan we had one of the first virtual memory machines, called the IBM Model 360/67. MTS was a timesharing system built to take advantage of the virtual memory architecture. It consisted of an executive system together with various programming languages and utilities. For many years it and its clones at University of Alberta in Canada and INRIA in Grenoble, France, served the faculty, staff and students.

What made the IBM 65 a 67 was a set of eight 32-bit dynamic address translation (DAT) registers between the CPU and memory. Compare this with today’s translation lookaside buffer (TLB), typically 16 kB or more. The IBM 67 at Michigan was actually two machines, each with a CPU, two core memory boxes, two I/O channels, eight 16-MB disk packs and sprinkled with tape drives and various controllers. Each six-foot tall corebox held 256 kB of oil-cooled core memory and burned 30,000 BTU. Today we get 64 coreboxes in a thumbnail-sized chip powered by a penlight battery.

This is the front panel and operator console of one of the CPUs. As you can see, IBM went nuts on incandescent lights for the various machine registers, but the only one that really mattered was the WAIT light, which lit when the machine wasn’t doing anything. That’s Mike Alexander sitting in front of the operator’s console. He was the principle architect of the executive system, today called the kernel. This was in fact the first virtual memory, multiple processor executive system and a groundbreaking system in its own right.

This is the configuration console for the dual CPU system. Either of four coreboxes and four channels could be switched to either CPU in any combination. We could and often did partition the hardware as two independent systems and ran MTS on one and IBM OS/360 on the other. Sometimes we even ran something called TSS/360, which was built by IBM but never finished. The huge book perched on the top is the Systems Reference Library, which held every little detail for maintenance and repair. At that time IBM was the second most prolific paper publisher after only the US Government. Even so, IBM print documentation was far superior in depth and quality compared with today’s online tutorials.

At that time every IBM mainframe came with a resident hardware engineer who fixed things on the spot, should something break. Before transistors, mostly what he did was replace 12AT7 vacuum tubes. Later as seen here, there wasn’t a lot to do except watch the log. By far the biggest worry was the air conditioner system. When it failed you had only a few minutes to kill the machine before alarms started off all over the room. One chilling Michigan night when I was alone with the machine and the air conditioner failed, I just opened the loading dock doors to the night and nature did the rest.

This is an IBM Model 1410. At the Computing Center it had only one mission in life: read Hollerith cards to magnetic tape for input to the IBM 67 and print magnetic tape output from that machine. As it happened, the card reader and line printer were really fast, considering the huge quantity of cards and paper then used for program input and output. Before our habits turned to video displays, a large computing center like ours consumed paper in the range of fractional forests per day. See the Anatomy of a Hollerith Card gallery for long forgotten technology of that era.

This is an IBM 2260 Video Display Unit, once the glass teletype of choice for a timesharing system. It had a bilious green phosphor and for some strange reason scanned from top to bottom then from left to right. One of my jobs was to adapt a standard TV set to the 2260 video signal, so we could use it to display current batch job status. It turned out to be more than just rotating the CRT yoke 90 degrees.

This is an IBM 2703 Transmission Control Unit, at one time the only choice for an IBM customer to run a moderate to large number of remote terminals. It was clumsy, unforgiving and slow and the timesharing users hated it. I took on the job as chief designer for a team which built something better; see the Data Concentrator Project gallery for the results.